Darren Wilson and the Protocols of Official Exonerationby William Norman GriggNov. 25, 2014 |

Popular

Ben Shapiro, Mark Levin and Laura Loomer Warn of Foreign Influence... From Qatar

NYT: Trump Ended War With Houthis After They Shot Down U.S. Drones, Nearly Hit Fighter Jets

Eloy Adrian Camarillo, 17, Arrested in Shooting Death of Infowars Reporter Jamie White

Trump Advisor to Washington Post: 'In MAGA, We Are Not Bibi Fans'

Trump Cut Off Contact With Netanyahu Over 'Manipulation' Concerns, Israeli Reporter Claims

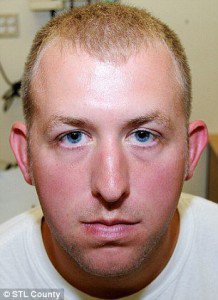

The most important details in Darren Wilson’s grand jury testimony come on pages 77-78 of the transcript. Asked if he had filled out an incident report on the shooting, Wilson explained that the “protocol” in such cases is to “contact your FOP [Fraternal Order of Police] representative and he will advise you of what to do step by step.” The most important details in Darren Wilson’s grand jury testimony come on pages 77-78 of the transcript. Asked if he had filled out an incident report on the shooting, Wilson explained that the “protocol” in such cases is to “contact your FOP [Fraternal Order of Police] representative and he will advise you of what to do step by step.”When asked if he had committed his recollections to paper in a diary or journal, Wilson replied: “My statement has been written for my attorney.” “And that’s between you and your attorney, then?” asked the exceptionally helpful prosecutor, who received an affirmative reply. “So no one has asked you to write out a statement?” the assistant DA persisted. “No, they haven’t,” Wilson acknowledged. Like anybody else suspected of a crime, Wilson was presumed innocent and could not be forced to incriminate himself. Unlike a Mundane suspected of homicide, however, Wilson was given the luxury of crafting his story to fit subsequent disclosures, in consultation with a police union attorney who added the necessary melodramatic flourishes. Thus we are told that when Wilson grabbed Brown’s forearm through the window of his SUV, “the only way I can describe it is I felt like a five-year-old holding on to Hulk Hogan.” Although the 18-year-old Brown possessed nearly 300 pounds of unathletic girth, Wilson was no nebbish: Like Brown, he stands 6’4″ and weighs 210 pounds. After being shot during the altercation in the SUV, Brown displayed the face of a “demon,” Wilson claims. After fleeing from the officer, who continued to shoot at him, Brown could be seen “almost bulking up to run through the shots,” Wilson continued, a line that doubtless reflects the verbal artistry of a well-paid police union attorney. Like others accused of a crime, Wilson had the right to counsel of his choice. In his case, however, a defense attorney was redundant. The grand jury transcript from September 26 listed the case as “State of Missouri vs. Darren Wilson,” but the assistant St. Louis County District Attorneys who examined the suspect behaved more like defense attorneys than prosecutors. Their advertised task was to determine if probable cause existed to justify criminal charges against Wilson for the shooting of tardily identified robbery suspect Michael Brown. The actual function they performed was to rationalize the killing in a way that would bring about Robert McCullouch’s intended result, the no-billing of the former police officer. When a prosecutor actually seeks an indictment, he will not go to the trouble of presenting potentially exculpatory evidence. In fact, as former federal prosecutor Sidney Powell documents in her infuriating new book Licensed to Lie, prosecutors generally go through heroic contortions to withhold, disguise, misplace, or exclude “Brady” material. McCullouch, a prosecutor not known for his solicitude toward the accused unless they are swaddled in the vestments of the State’s coercive caste, made a point of making the case for the defense, which is a function usually carried out during a criminal trial by counsel for the defendant. At various points in the 92-page transcript, we can see how McCullough’s carefully guided Wilson through his testimony, prompting him to follow the script provided by his police union attorney, and either ignoring or gently correcting him when caught in the kind of contradictions upon which a motivated prosecutor would triumphantly seize. For example: Wilson claimed that at one point, Brown had “complete control” over the officer’s firearm. Under the kind prompting from one of the unusually solicitous assistant DAs, Wilson admitted that the gun never left his hand, and that his was the finger on the trigger. Wilson states that after he confronted Brown and Johnson (whom he did not identify as robbery suspects until after the initial contact) for jaywalking, Brown’s hostile attitude prompted him to call for backup and then cut them off with his police vehicle. When he tried to leave the vehicle, Brown allegedly shoved the car door shut and glared at the officer with an “intense face” as if intending to “overpower” him. At some point — Wilson isn’t clear on the details — Brown supposedly slugged the officer through the window. Reciting a well-rehearsed script, Wilson told the jurors that he scrolled through non-lethal options before pulling his gun. “Get back or I’m going to shoot you,” Wilson says he told Brown. At this point “He immediately grabs my gun and says, `You are too much of a pussy to shoot me,’” the officer claimed. Later in his testimony, Wilson elaborated: “He didn’t pull it from my holster, but whenever it was visible to him, he then took complete control of it.” Wilson threatened to kill Brown; Brown refused to be shot. This complicates the self-defense claim, which rests on Wilson’s assertion that by this time he had been struck twice by the behemoth, and was afraid that “the third one could be fatal if he hit me right.” Yet despite being repeatedly pummeled by a man-mountain of preternatural strength — a veritable Hulk Hogan, if not an Incredible Hulk — Wilson’s face displayed no visible injuries. The alleged blows were sufficient to justify lethal force, even against a fleeing, unarmed suspect, Wilson insists. “My gun was already being presented as a deadly force option while he was hitting me in the face,” he told the jurors, later saying that hurling lead down a residential street was justified in order to “protect” the public from an unarmed suspect who had assaulted an armed police officer. Michael Brown was apparently a shoplifter and a bully. If this was the case, he should have been compelled to make restitution to the victims. (Interestingly, although Wilson claimed to have seen stolen cigarillos in Brown’s hands during the “assault,” they were never found.) While there’s no clear evidence that Brown ever assaulted Wilson, it is indisputable from Wilson’s testimony that he was the one who escalated the encounter by threatening lethal force. This is problematic even under positivist legal precedents: Per Bad Elk vs. US, Brown — even as a criminal suspect — didn’t have a duty to die simply because Wilson had the means to kill him, and according Tennessee vs. Garner Wilson didn’t have the legal authority to kill Brown simply because he tried to evade arrest. One needn’t consider Michael Brown to be a winsome innocent in order to believe that Wilson’s conduct in this incident was, at best, thoroughly suspect — and suitable for examination in a genuinely adversarial process of the kind Robert McCullouch was determined to avoid. |