Armed and Black: The History of African-American Self-Defenseby B.K. MARCUSThe Freeman Feb. 04, 2015 |

Popular

Rep. Randy Fine: Pro-Palestine Movement Are 'Demons' Who 'Must Be Put Down by Any Means Necessary'

ADL Responds to DC Shooting With Call to Deplatform Twitch Streamer Hasan Piker

Israeli PM Netanyahu: Trump Told Me 'I Have Absolute Commitment to You'

Trump Confronts South African President on White Genocide

CNN: U.S. Officials Say Israel Preparing Possible Strike on Iran

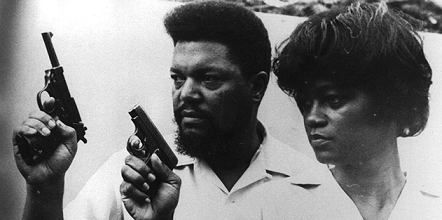

In Dallas, Texas, the newly formed Huey Newton Gun Club marches in the streets bearing assault rifles and AR-15s. "This is perfectly legal!" the club leader shouts. "Justice for Michael Brown! Justice for Eric Garner! … Black power! Black power! Black power! Black power!" Meanwhile, closer to Washington, DC, the venerable National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) responds to the fatal shooting of two New York City police officers in December by repeating its call for tougher gun-control laws. How, then, do black Americans feel about guns?  They are divided on the issue, as are Americans generally. But that doesn’t mean they’re evenly divided. The 21st-century NAACP represents what one black scholar calls "the modern orthodoxy of stringent gun control," whereas the members of the Huey Newton Gun Club are a minority within a minority, as were the Black Panthers of the 1960s, from whose founder the gun club takes its name. It turns out, however, that the gun-toting resistance may better represent the traditional majority among the American descendants of enslaved Africans — including the original NAACP. Peaceful people with guns An older and deeper tradition of armed self-defense "has been submerged," writes scholar Nicholas Johnson, "because it seems hard to reconcile with the dominant narrative of nonviolence in the modern civil-rights movement." It is the same tension modern-day progressives see in libertarians’ stated principles. Advocates of the freedom philosophy not only see our principles as compatible with gun rights; we see those rights as an extension of the principles. For a government (or anyone else) to take guns away from peaceful people requires the initiation of force. “But,” progressive friends may object, “how can you talk of peaceful people with guns?” What sounds absurd to them is clear to the libertarian: the pursuit of "anything peaceful" is not the same as pacifism. There is no contradiction in exercising a right of self-defense while holding a principle of nonaggression. In other words, we believe peaceful people ought not initiate force, but we don’t rule out defending ourselves against aggressors. And while a few libertarians are also full-blown pacifists who reject even defensive violence, that does not mean they advocate denying anyone their right to armed self-defense (especially as such a denial would require threatening violence). The black tradition of armed self-defense For more than a hundred years, black Americans exemplified the distinction above when it came to gun rights. The paragon of black nonviolence, Martin Luther King Jr., explained it eloquently: Violence exercised merely in self-defense, all societies, from the most primitive to the most cultured and civilized, accept as moral and legal. The principle of self-defense, even involving weapons and bloodshed, has never been condemned, even by Gandhi.King not only supported gun rights in theory; he sought to exercise those rights in practice. After his home was firebombed on January 30, 1956, King applied for a permit to keep a concealed gun in his car. The local (white) authorities denied his application, claiming he had not shown "good cause" for needing to carry a firearm. Modern advocates of gun-control laws will point out that King ultimately regretted his personal history with guns, seeing them as contrary to his commitment to nonviolence, but King understood that his pacifism was not in conflict with anyone else’s right to self-defense. According to his friend and fellow activist Andrew Young, "Martin’s attitude was you can never fault a man for protecting his home and his wife. He saw the Deacons as defending their homes and their wives and children." The Deacons for Defense and Justice was a private and well-armed organization of black men who advocated gun rights and protected civil rights activists. Even after the Deacons became a source of embarrassment to many in the nonviolence movement, King maintained his support. "Martin said he would never himself resort to violence even in self-defense," Young explained, "but he would not demand that of others. That was a religious commitment into which one had to grow." While King may have come to see his strategic nonviolence as being of a piece with personal pacifism, most activists in the civil rights movement saw no contradiction between nonviolent strategy and well-armed self-defense. "Because nonviolence worked so well as a tactic for effecting change and was demonstrably improving their lives," writes Charles E. Cobb Jr., a former field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), "some black people chose to use weapons to defend the nonviolent Freedom Movement. Although it is counterintuitive, any discussion of guns in the movement must therefore also include substantial discussion of nonviolence, and vice versa." Voting-rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, for example, advised blacks to confront white hatred and abuse with compassion — “Baby you just got to love ’em. Hating just makes you sick and weak.” But when asked how she survived when white supremacists so often grew violent, Hamer replied, “I’ll tell you why. I keep a shotgun in every corner of my bedroom and the first cracker even look like he wants to throw some dynamite on my porch won’t write his mama again.” Black history In Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms, Johnson shows that the attitudes of King and Hamer go back for well over a century in the writings, speeches, and attitudes of black leaders, even when their libertarian attitude toward firearms was at odds with the philosophy of their white allies. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave and the most famous black leader of the 19th century, rejected the pacifism of his white abolitionist supporters when he suggested that a good revolver was a Negro’s best response to slave catchers. Harriet Tubman, the celebrated conductor of the Underground Railroad, offered armed protection to the escaped slaves she led to freedom, even as they sought sanctuary in the homes of Quakers and other pacifist abolitionists. Lest you think religious devotion divided the black community on this subject, a mass church gathering in New York City in the mid-19th century resolved that escaped slaves should resist recapture “with the surest and most deadly weapons.” W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the cofounders of the NAACP in 1909, wrote of his own response to white race riots in the South: “I bought a Winchester double-barreled shotgun and two dozen rounds of shells filled with buckshot. If a white mob had stepped on the campus where I lived I would without hesitation have sprayed their guts over the grass.” If that sounds like simple bloodlust, consider that Du Bois outlined for his readers an understanding of armed violence that should resonate with advocates of the nonaggression principle: “When the mob moves, we propose to meet it with bricks and clubs and guns. But we must tread here with solemn caution. We must never let justifiable self-defense against individuals become blind and lawless offense against all white folk. We must not seek reform by violence.” Du Bois was not at odds with the larger organization for which he worked. “While he extolled self-defense rhetorically in the Crisis,” writes Johnson, “the NAACP as an organization expended time, talent, and treasure to uphold the principle on behalf of black folk who defended themselves with guns. That fight consumed much of the young organization’s resources.” Yes, the NAACP originally devoted itself to defending precisely those same rights that it now consistently threatens. These examples all predate the nonviolent civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s. But as King’s own words show us, support for armed self-defense continued well into the civil rights era. In fact, Charles Cobb argues in This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible, the success of the civil rights movement depended on well-armed blacks in the South. Cobb writes that the “willingness to use deadly force ensured the survival not only of countless brave men and women but also of the freedom struggle itself.” The victories of the civil rights movement, Cobb insists, “could not have been achieved without the complementary and still underappreciated practice of armed self-defense.” Even Rosa Parks, quiet icon of both civil rights and nonviolent resistance, wrote of how her campaign of peaceful civil disobedience was sustained by many well-armed black men. Recalling the first meeting of activists held at her house, Parks wrote, “I didn’t even think to offer them anything — refreshments or something to drink.… With the table so covered with guns, I don’t know where I would’ve put any refreshments.” The guns didn’t go away after her victory in the Supreme Court. “The threatening telephone calls continued.… My husband slept with a gun nearby for a time.” The origins of gun control, public and private In contrast to the rich black history of peacefully bearing arms, the earliest advocates of gun control in America were Southern whites determined to disarm all blacks. In 1680, the Virginia General Assembly enacted a law that made it illegal for any black person to carry any type of weapon — or even potential weapon. In 1723, Virginia law specifically forbade black people to possess “any gun, powder, shot, or any club, or any other weapon whatsoever, offensive or defensive.” These were laws from the colonial era, but even after the Second Amendment, we see the same pattern: Southern whites who reacted to the abolition of slavery “through a variety of state and local laws, restricting every aspect of Negro life, from work to travel, to property rights.” Johnson explains that “gun prohibition was a common theme of these ‘Black Codes.’” Where the Black Codes fell short in their effectiveness, the Ku Klux Klan and an array of similar organizations "rose during Reconstruction to wage a war of Southern redemption.… Black disarmament was part of their common agenda." But while many white people were opposed to the idea of black people with guns, black support for gun rights, according to Johnson, "dominated into the 1960s, right up to the point where the civil rights movement boiled over into violent protests and black radicals openly defied the traditional boundary against political violence." That violent and radical turn was the catalyst for a dramatic transition, as the movement ushered in a new black political class. Rising within a progressive political coalition that included the newly minted national gun-control movement, the bourgeoning black political class embraced gun bans.… By the mid-1970s, these influences had supplanted the generations-old black tradition of arms with a modern orthodoxy of stringent gun control.Top-down versus bottom-up In every large group, there is a division of interests, understanding, and goals between an elite and the rank and file. In American history, those of African descent have been no different in this regard. But for most of that history, the black leadership and the black folks on the ground have been in agreement about the importance and legitimacy of armed self-defense — and equally suspicious of all attempts by any political class to disarm average people. According to the new orthodoxy, however, any preference that black people demonstrate for personal firearms cannot represent the race — only a criminal or misguided subset. So the black political class consistently supports disarming the citizenry, both black and white — although remarkably, some are even willing to target gun bans to black neighborhoods. But while the black elite tries to plan what’s best for the black rank and file, some individuals are rejecting the plan and helping to drive history in a different direction. "Recent momentous affirmations of the constitutional right to keep and bear arms," writes Johnson, "were led by black plaintiffs, Shelly Parker and Otis McDonald, who complained that stringent gun laws in Washington, DC, and Chicago left them disarmed against the criminals who plagued their neighborhoods." What do we make of these rebels? Are they traitors to their race? Are they dupes of the majority-white gun lobby? Or were they, as Cobb describes Southern blacks of the 1960s, "laying claim to a tradition that has safeguarded and sustained generations of black people in the United States"? Neither Parker nor McDonald will be nominated for an NAACP Image Award any time soon, but perhaps they represent a different black consciousness — a more individualist, even libertarian, tradition with a stronger grounding in black history. _ B.K. Marcus is managing editor of The Freeman. |