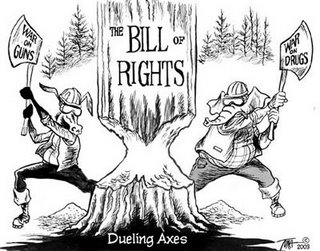

How The "War On Drugs" Brought Communism To AmericaWilliam N. GriggSep. 25, 2007 |

Popular

Claim Jewish Student Was 'Stabbed In The Eye' by Pro-Palestine Protester Draws Mockery After Video Released

Senate Passes $95B Giveaway to Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan, Combined With TikTok Ban

Biden Signs Bill to Give $95B to Israel, Ukraine and Taiwan, Ban TikTok

'These Protesters Belong in Jail': Gov. Abbott Cheers Arrest of Pro-Palestine Protesters at UT Austin

Mistrial Declared in Case of Arizona Rancher Accused of Killing Migrant Trespasser

Alan and Stephne Roos of Bothell, Washington are victims of Communism. The couple -- a butcher and dental assistant, respectively -- lost their automobiles to the officially sanctioned form of theft called "asset forfeiture" because their 24-year-old son Thomas has used them to conduct drug transactions. Alan and Stephne Roos of Bothell, Washington are victims of Communism. The couple -- a butcher and dental assistant, respectively -- lost their automobiles to the officially sanctioned form of theft called "asset forfeiture" because their 24-year-old son Thomas has used them to conduct drug transactions.Neither Alan nor Stephne has been charged with a crime of any kind. Under the Communist premises of the "War on Drugs," it isn't necessary to be convicted of a crime in order to lose one's property, since the State is empowered to seize anything its agents wish to steal, at any time they wish to do so, as long as some "drug nexus" can be established to justify the theft. The theory and practice of Communism are based on the denial of private property, and the administration of "justice" under Communism is collectivist in nature. It is not necessary to prove the guilt or innocence of an individual accused of a crime against socialism, explained Lenin shortly after the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917; it is sufficient to demonstrate that the accused belongs to a collective regarded as an enemy of the State. Once this is understood, it becomes clear that Communism came to America -- in principle, if only intermittently in practice -- in 1970 with the passage of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. That measure nullified the right of private property by permitting law enforcement to steal (or "forfeit") money and physical assets believed to be involved in, or the proceeds of, narcotics trafficking. The very term "forfeiture" carries a connotation that property rights are contingent and can be revoked when those acting on behalf of the State choose to do so. Under the Anglo-Saxon tradition of liberty under law, property can be taken only following due process of law; this would require a criminal proceeding in which the accused are presumed innocent until proven guilty of a specific offense and convicted by a jury of their peers. None of this is true where "asset forfeiture" is concerned. Under the first Bush administration, which was led by a former CIA Director (every individual holding that post is also the Kingpin-in-Chief ex officio of the global narcotics trade), a model anti-drug statute was created in Washington, D.C. and sent out to various state legislatures. The seizure and forfeiture provision in Washington State's version of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act is typical of laws governing the practice throughout the country, and the same is true of the forfeiture mechanism created by that statute. The experience endured by Alan and Stephne Roos could happen to anyone living in the USSA. Thomas Roos, who had already served six months in jail on drug-related charges, was pulled over repeatedly in 2005 by police who found evidence of illegal drug transactions. In August of that year the local counter-narcotics soviet, called the Snohomish Regional Drug Task Force (SRDTF), "forfeited" the family's late-model Nissan. Following another arrest, the SRDTF stole the second vehicle, a refurbished 1970 Chevy Chevelle "muscle car." Alan and Stephne insist that they didn't know that their son was using the cars to conduct drug transactions, and that they were furious with him for doing so. They explained as much to the "designated hearing officer" for the County Sheriff's Department, who ruled that a "preponderance of evidence" existed that the cars had been used for drug trafficking. Once that decision was made -- not by a jury, or a judge, but by an official of a Sheriff's Department that stood to profit from the seizure -- Alan and Stephne were informed that they had the burden to prove that they weren't aware of Thomas' activities in order to receive the "benefit" of the "innocent owner exception." In other words: Once the police stole Alan and Stephne's cars, what had been a right was transmuted into a contingent, government-granted "benefit." The Washington State statute specifies that "no property right exists" in assets that are stolen by the government in this fashion. And in order to qualify for the exception, Alan and Stephne, like all others in such a predicament, were required to prove their innocence -- not regarding a criminal act, mind you, but regarding what the state Court of Appeals called their "mental state." Not surprisingly, given that (once again) the hearing officer worked for the department that had already stolen the cars, and had every reason to justify that theft, ruled against Alan and Stephne, insisting (in the words of the state Court of Appeals) "substantial evidence supported a finding that Alan and Stephne knew or should have known that Thomas was using the vehicles to acquire possession of drugs." In upholding the theft of Alan and Stephne's property, the Court of Appeals pontificated that the "innocent owner exception" in an asset forfeiture applies only when "the claimant is able to demonstrate that the illegal activity for which the vehicles was used was undertaken without the claimant's knowledge or consent." Add the "War on Terror" to that roster for the totalitarian trifecta. If Alan and Stephne knew about, or consented to, Thomas' use of their cars to deal drugs, why weren't they charged as either co-conspirators or accessories, before their property was seized by the State? But comrade, that's how the justice system works in bourgeois countries still groaning beneath retrograde, delusional concepts such as the sanctity of private property and the rights of the accused. The belief in Due Process of Law was the opiate of the masses, and eliminating that opiate was the central -- albeit unspoken -- objective in the Grand And Glorious War On Drugs. _____________ Be sure to visit The Right Source and the Liberty Minute archive. Labels: police state; war on drugs; private property |