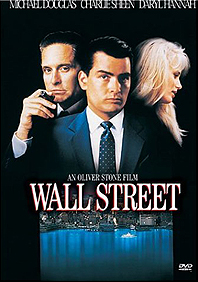

Gordon Gekko, Michael Milken, and Meby Doug Casey, Liberty Magazine 1991Sep. 25, 2010 |

Popular

Report: Blinken Sitting On Staff Recommendations to Sanction Israeli Military Units Linked to Killings or Rapes

America Last: House Bill Provides $26B for Israel, $61B for Ukraine and Zero to Secure U.S. Border

Bari Weiss' Free Speech Martyr Uri Berliner Wants FBI and Police to Spy on Pro-Palestine Activists

'Woke' Google Fires 28 Employees Who Protested Gaza Genocide

John Hagee Cheers Israel-Iran Battle as 'Gog and Magog War,' Will Lobby Congress Not to Deescalate

[Extracted from 'Liberty Magazine' from 1991, Doug Casey has quite a different take on the movie "Wall Street" !] [Extracted from 'Liberty Magazine' from 1991, Doug Casey has quite a different take on the movie "Wall Street" !]Judging by what's been going on in the financial markets recently, there's a lot of confusion on the subject of insider trading. It's getting harder and harder to know what's right and what's wrong. So, to get my philosophical bearings, I naturally turned first to our national repository of wisdom and moral rectitude: the popular media. The media's definitive statement on these matters in recent years-and an accurate reflection of the public's attitude as well--can be found in the 1986 movie Wall Street. Let's go to the movies! Wall Street: The Movie As you'll recall, the movie chronicles the rise of a young stockbroker named Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen) as he becomes a protege of corporate raider / speculator Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas), his supposed corruption in the process, and his subsequent "return to grace." On a psychological level it's the story of how a "good guy" (exemplified by Fox's father) and a "bad guy" (Gordon Gekko) vie for moral possession of Bud's soul. Bud's father-an unintelligent, pigheaded loser of a populist union steward-mentions that the FAA is going to exonerate his employer, Blue Star Airlines, for an accident; he gratuitously allows how he always had believed it was "those greedy cost-cutting" airplane manufacturers who were really to blame. This view provides a good clue to the filmmakers' values. Another is offered when the elder Fox originates: "The only difference between the Empire State Building and the pyramids is that the Egyptians didn't have unions." Sure. And the only difference between McDonald's and a bread line in the Gulag is the sesame seed buns. Knowledge of the unannounced FAA decision is valuable to a stock trader, so Bud wangles an appointment with Gekko, using a box of Cuban cigars (which his straight-arrow dad must have liberated with a bribe to a customs inspector) as a door-opener. Bud discloses the Blue Star decision to Gekko, who naturally buys the stock in anticipation, making a bundle. This is presented as an illegal and unethical use of inside information. Was it illegal? Who knows? The very concept of inside information is undefined and undefinable. The rationale against insider trading is to create a "level trading field" for all players, so no one knows anything before anyone else and there are no "unfair" advantages. Would it have been illegal if Fox had, instead of telling just one person, taken out an ad in The Wall Street Journal to inform the world at large? What about those who didn't read the paper that day; would they have grounds for a lawsuit claiming they were somehow injured because they didn't get to buy? That's up to the whim of some regulator to decide. Shouldn't it also be "inside information" if the few people who hear an official announcement first get to act on it first? What if Gekko just had a definite hunch about the decision and bought Blue Star based on that alone; how could he prove he didn't have illegal data? The concept of inside information is a witch hunter's dream. It's a natural for envy-driven losers, government lawyers, and the like. Was Gekko's stock purchase ethical? Absolutely, since the information was honestly gained. Next, Gekko convinces Bud to tail an Australian speculator around town so that he can figure out what stocks the Australian is planning to buy, and buy them first. Bud asks, "That's inside information, isn't it?" before embarking on field research that results in more successful trades. Is it inside information to follow someone around and conjecture what he's likely to buy based on who he visits? I can't see how it could be construed this way; again, it's information honestly acquired. Next Bud gains access to a law office, posing as a cleaning man, and copies some files detailing a takeover. Inside information? I don't know. But it certainly is theft. The movie is unable to draw a distinction between detective work and theft. The fact that a theft-a real, common law crime, the only one mentioned in the whole movie-has been committed is never once even mentioned. A Hero in the Slime It's hard to keep your attention on the vapid, dishonest little yuppie played by Charlie Sheen. The real focus is on the dynamic Gordon Gekko. He is not a particularly nice guy; he cheats on his wife, is very materialistic, and he doesn't give suckers an even break. And he probably doesn't care where or how Bud gets his information. But do you care where Standard and Poor's gets its data? No. You only care that it's accurate. Gekko encourages Bud to get information that isn't common knowledge; that's what makes for success in many legitimate endeavors. He never encourages Bud to become a criminal. In fact, Gekko never does anything unethical throughout the whole movie except lie to the union people when he's about to take over Blue Star at the end. Other than that one instance, one can make a case that Gekko is actually a moral hero. Look at the facts, not the nasty patina with which the film paints him: Gekko rewards Bud for doing what appears to be good work; there is always fair exchange. Gekko's infamous "greed is good" speech at the annual general meeting of Teldar Paper could have been written by Ayn Rand. Gekko explains how money is congealed life, representing all the good things one ever hopes to have and provide. Love, life and money are all good. And since they're good, so's the desire-the greed-to have as much of them as possible. The episode also illustrates why takeovers are usually a good thing. Gekko points to Teldar's dozens of vice-presidents being paid six figures to shuffle memos and build little satrapies with money that should be dividended out to the shareholders, and Gekko makes it clear that if he wins they'll be fired. He's absolutely right, and his actions through-out the movie can only serve to better the lot of thousands, maybe millions, of people. Nonetheless, Bud is rightfly soured by Gekko's lie about Blue Star and he decides to turn state's evidence on Cekko after being landed upon by the SEC for some of his dealings. Bud wires himself, presumably to get a reduced sentence, and induces Gekko to say compromising things. It's at this point that the only morally unambiguous and satisfying point in the whole movie is made: Gekko, quite correctly, beats the daylights out of the sleazy little creep. The hateful movie ends with young Bud having completely caved in to the ethical morass personified by his father. He says, ''Maybe I can learn how to create, instead of living off the buying and selling of others." Maybe he's planning to retire to a hippie commune to make candles and baskets. Maybe he'd prefer Cuba, where most forms of buying and selling are illegal. Try defending Gekko sometime, and watch the reaction you get; it's like trying to defend Hitler. People seem to have a very hard time making a distinction between their emotional reaction to a situation and the actual rights and wrongs involved. It's strange how seldom most .people analyze moral issues; for many, an act is wrong just because a preacher or an official says it is. They rarely question whether people in positions of authority might have based their judgments on false premises or have a hidden personal agenda. Something is accepted as being wrong simply because everyone assumes it is, and after a while that unchallenged assumption becomes part of the social contract, from top to bottom. This stuff works in funny ways; now "Gordon Gekko" and everything he's supposed to stand for has become a cultural shorthand for all that's wrong with the U.S. financial system. Ivan Boesky, the greatest inside dealer of the '80s, is a pariah, but not because he wired himself for many months, compromising his closest friends and associates in exchange for a reduced sentence. Rather he is ostracized because he used "inside information" to trade. Whether it was gained honestly or not (probably not, considering the basic character of the man) was never made clear; but that, apparently, was never even an issue. This kind of thing has major implications for the markets over the long run. In that light, it's worth taking an in-depth look at that great real-life villain of the financial community, Michael Milken. Michael Milken as a Role Model I presume you're as sick as I am of hearing the press decry the greed that supposedly characterized the '80s. It's not greed if a politically correct Jane Fonda or Bruce Springsteen makes $50 million in a year, but it is if a stockbroker makes that much. I'm a freedom fighter, you're a rebel, he's a terrorist. Milken was the object of an intensive government investigation that took hundreds of thousands of man hours and cost many millions of· dollars. It became a political issue with a life of its own. Milken had to be punished for something, somehow. After all, we can't have somebody who made $500 million in a year live happily ever after, especially if he earned it honestly. Read the Rest in Liberty Magazine Here (.pdf) |