65 years later, his questions lingerMan aboard USS Boise saw fleet that later bombed Pearl HarborBy ED SEALOVER Colorado Springs Gazette Dec. 10, 2006 |

Popular

Mistrial Declared in Case of Arizona Rancher Accused of Killing Migrant Trespasser

Sen. Hawley: Send National Guard to Crush Pro-Palestine Protests Like 'Eisenhower Sent the 101st to Little Rock'

Claim Jewish Student Was 'Stabbed In The Eye' by Pro-Palestine Protester Draws Mockery After Video Released

AP: 'Israeli Strikes on Gaza City of Rafah Kill 22, Mostly Children, as U.S. Advances Aid Package'

Senate Passes $95B Giveaway to Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan, Combined With TikTok Ban

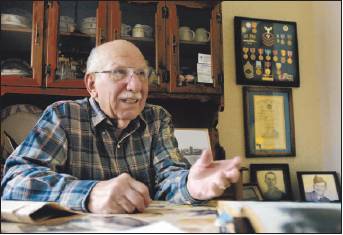

Around this time every year, Joe Fenton’s mind wanders back to the preview he had of the destruction that would be unleashed on Pearl Harbor. Around this time every year, Joe Fenton’s mind wanders back to the preview he had of the destruction that would be unleashed on Pearl Harbor.Just 17 years old and six months removed from boot camp, Fenton was an oiler on the USS Boise as it escorted five merchant ships carrying air base construction materials across the Pacific to the Philippines. After midnight on the morning of Nov. 28, 1941, the light cruiser’s loudspeakers blared with orders for crew members to man their battle stations. Fenton scrambled to the deck and saw two dozen ships of unknown origin about 3 miles away on the horizon, heading east. They were silhouetted by moonlight that would have blinded the fleet to the Boise’s presence. Greatly outnumbered and under orders to maintain radio silence, the Boise did not fire and did not alert anyone for days to what it had seen. When the Boise reached Manila, officers alerted members of Gen. Douglas Mac-Arthur’s staff of their find, Fenton said. Their reaction, as he recalled, was: “They’ve got as much right to be in the water as we do.” It was only when word came down Dec. 7 about the Pearl Harbor attack that Fenton and his shipmates realized they had seen the fleet that brought America into World War II. While the Boise hid by a remote Pacific island after the attack and awaited orders, talk buzzed about what its crew could have done. That conversation has dimmed today; most crew members have passed away. But Fenton, a retired Colorado Springs plumbing company owner, replays the talk to himself. “I always think that perhaps we could have prevented the whole thing . . . if we had got the alarm off,” the 82-year-old said last week in his kitchen. “I always think: ‘Maybe I could have prevented this.’ I get real sad about it.” But he said that thought is followed quickly by the realization that if the Boise had made any move that could have alerted the Japanese it had seen them, the fleet would bombarded it into the pages of history. “I think the whole picture of World War II would have changed if we had just gotten a radio off,” he added. “But it would have cost my life.” Memorial events across the country will mark the 65th anniversary today of the early morning raid that killed about 2,500 Americans. Some people will head to Hawaii to honor the occasion; others will gather at local monuments. Fenton will be in Colorado Springs, surrounded by newspaper clips and medals that mark his Navy service and, later, the Army. His thoughts, though, will be on what he saw in the middle of the ocean. No one present forgot that moment, which has been little recorded in history. Melvin Howard, a former crewman and current Philadelphia resident who once chaired reunions for the Boise, remembered that everyone on the ship was ready to fire if ordered. “We never got the word to fire,” Howard said. “And it’s a good thing we didn’t, because they would have blown us out of the water.” Once America entered the war, the Boise made 14 landings in the Pacific and in Europe, fought in the Battle of Guadalcanal and served as a scout vessel before the famed Doolittle Raid on Tokyo. The Boise earned its greatest accolades by sinking six Japanese ships in 27 minutes off Cape Esperance in 1942. Despite a shell crashing through a part of the ship in which he was working, Fenton, who fed oil into boilers and later was a ship engineer, remembers staying calm. His mother, who raised him in Denver, saved newspaper articles about the ship and gave them to him in a scrapbook when he returned. Fenton also kept a diary during his service, and he typed it up in recent years to preserve it. “Did not know what was going on, we were not at war, the ships all stopped and our gun turrets all trained to our port side,” he wrote of the November 1941 sighting. “That makes you wish you had gone to the bathroom a little earlier.” After being transferred to the Army and serving a short stint in Asia during the Korean War, Fenton started a business in Colorado Springs. He ran Fenton Plumbing and Heating until retirement in 1982, when he passed the company on to his son. He stops there for coffee every once in a while, and he carves wood figures for his family and friends. Twice widowed, the decorated veteran spends every Friday night dining and dancing at the Veterans of Foreign Wars post with his girlfriend. Late 1941 is not that far away, though. Any mention of Pearl Harbor sparks thoughts of that day, and any thought about what he saw leads him to think even more about what could have occurred. “They made no hostile moves to us,” Fenton said. “It was like two strangers passing in the night. We weren’t going to initiate the firing. There was no way we could have survived that.” |