The curse of the 9/11 widowsThe Daily MailSep. 06, 2006 |

Popular

Claim Jewish Student Was 'Stabbed In The Eye' by Pro-Palestine Protester Draws Mockery After Video Released

Mike Johnson Pushes Debunked Lie That Israeli Babies Were 'Cooked in Ovens' On October 7

Senate Passes $95B Giveaway to Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan, Combined With TikTok Ban

'These Protesters Belong in Jail': Gov. Abbott Cheers Arrest of Pro-Palestine Protesters at UT Austin

'It Has to Be Stopped': Netanyahu Demands Pro-Palestine Protests at U.S. Colleges Be Shut Down

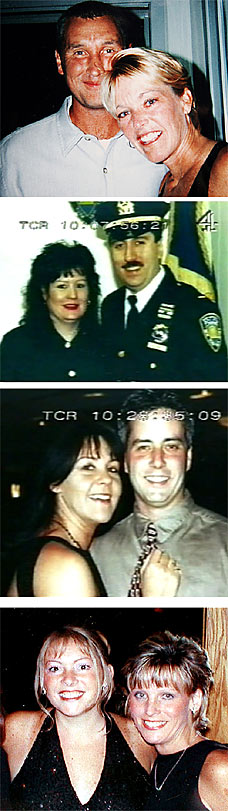

This was the lottery that nobody wanted to win. The day New York's Twin Towers were destroyed by hijacked planes, hundreds of widows were left destitute. As the full extent of the horror of 9/11 became evident, public donations poured in. This was the lottery that nobody wanted to win. The day New York's Twin Towers were destroyed by hijacked planes, hundreds of widows were left destitute. As the full extent of the horror of 9/11 became evident, public donations poured in. During the feverish days following the attack, Congress established a billion- dollar compensation fund, and grieving wives became overnight millionaires. No one could have known that for many of them, the money would destroy their lives once again, attracting jealousy, resentful relatives and making them even more depressed. Some would become squandering, spendaholic widows, their payouts fuelling addictions which could not replace the husbands they had lost. Others would become embroiled in legal battles with their families, their lives eaten up by bitterness. Some, vilified by the public, would even receive a cash windfall which attracted others' husbands. And, most pitifully, some would get very little at all - their spouses deemed worthy of only a pittance under a system which favoured the rich. Those who took the 'blood money' of up to $7 million each were banned from suing the government or airlines for further compensation, their rights stripped away. Now the widows' stories are being told for the first time in a graphic television documentary to be shown tonight on Channel 4. The partner of one victim of the terror attack says: 'The public must assume that these families have been taken care of and everything worked out great, not realising that in many cases things worked out horribly.' Eileen Cirri's husband was one of the 2,823 people killed in the 9/11 attack. Her immediate thought when she heard that the first plane had crashed into the North Tower at 8.46am was for her husband, Robert, a policeman. 'I remember it like yesterday,' she says. 'I was on my way to work when I heard of the attack, it felt like the longest ride in the world. When I got to my desk, I called his station. No one answered.' As she watched the second plane, United Airlines Flight 175, hit the South Tower at 9.03am, Eileen became increasingly distraught. Then the telephone rang. 'It was him calling me, and I was like: "Thank God!" she says. 'It was 9.24am. He said: "I love you very much." I said: "You just need to get out of there!" and he goes: "I have to do something!"' A policeman with more than 17 years' experience and a paramedic in his spare time, Robert told his wife that he was going to try to save people trapped in the North Tower. It would be the last conversation between the couple. 'He sounded very, very confident,' his widow recalls. 'I said: "Just be quick. I love you. I'll see you at home tonight." And I thought I was going to see him.' Half an hour later, Eileen watched the towers collapse live on television. She returned home and waited for Robert to call again. When the phone finally rang, it would change her life. Her husband died inside the North Tower when it fell down, although his body would not be found for another five months. He was discovered in rubble on a stairwell, and had been trying to carry a woman in a wheelchair to safety. When her husband's life was valued at $1.5 million by the Victim Compensation Fund in the months following his death, Eileen rejected the money. 'Covert and sneaky' 'Congress did a three-in-the-morning session when the country was still horrified, the Ground Zero fires still burning,' she says. 'I felt like it was covert and sneaky, and it was really targeted to bail out the airlines.' The financial awards were based on the victim's age and potential earnings. Senior master of the fund, Kenneth Feinberg, explains: 'Over the course of 33 months I met about 1,500 families. 'In calculating awards, the law decreed that I take into account pain and suffering. That was the first requirement. The second requirement was that I must take into account the economic circumstances of each claimant.' He adds: 'When I hear people say: "Mr Feinberg, you gave different amounts to every claimant, that's very un-American," I say: "It may not have been a good idea. Maybe everybody should have got the same amount. Congress didn't allow that. But it's very American!"' The dependants of cleaners through to stockbrokers received between $250,000 and $7 million. The average award was $1.6 million - tax-free - but the widows of high-earners became instant multi-millionaires. In the event, 65 families litigated, while eight, perhaps overcome with grief, did not claim at all. 'I'm not placing a value on the intrinsic moral worth of any victim,' says Feinberg. 'I'm not saying that "Mr Jones" who died was worth more as a human being than "Mrs Smith".' Yet that was precisely how the news that her husband was in line for a bottom-of-the-scale payment felt to Eileen. 'I'm angry because people should have been compensated equally,' she says. 'I'm a strong advocate of that.' A feisty, dignified woman of 45, Eileen also objected to having her right to sue the authorities or airlines removed, and refused the award. Robert's children - by his first marriage - wanted to take the compensation, and launched their own action against Eileen. They argued that if she lost a legal case against the fund, they could end up with nothing. 'Knife in the back' 'When I got a lawsuit in the mail, it was just such a knife in my back,' she says. After three years of wrangling, Eileen's step-children won their case, and she was forced to enter the fund - eventually getting $3 million for the family. Feinberg assumed that once families received their money, they could move on with their lives, but women such as Eileen were too griefstricken to do so. 'This man was a treasure to me. He was much loved,' she says. 'But it was as if I was being told to shut up and take the money.' Those who willingly accepted the compensation also found that it brought little solace. Kathy Trant made national news headlines when her spending spree turned her into a celebrity. An attractive blonde, she has reportedly spent $5 million in the past five years, including £300,000 on designer shoes, £1,000 on Botox injections for friends and thousands of dollars on breast enlargement surgery. James Langton, a writer who has followed the fate of the 9/11 widows, says: 'Kathy is one of the loneliest people I've ever met. She told me that in the middle of the night, when she wakes up surrounded by all of these possessions, she just has this emptiness because that's really not what she wants. What she wants is her husband back.' Kathy, who was the focus of an entire Oprah Winfrey show and much criticism at the height of her spending spree, describes the awful void which she tries to fill. 'I'm dying inside,' she says. 'Every day when I read something that really bothers me I get so frustrated I go out and I shop because it's the only thing that makes me feel good.' She is battling depression and facing an uncertain future with her children Jessica, 23, Daniel, 17, and 14-yearold Alex. Another woman's story captured the public imagination for different reasons. When Madeleine Bergin's husband, John, died in the 9/11 attack, she became a fireman's widow. She received a million-dollar payout, and married her liaison officer and John's best friend in the fire service, Jerry Koenig, who left his wife, Mary, for her after ten years of marriage. Mary believes that Madeleine's payout was part of the attraction for her philandering ex-husband. 'I don't know when it [the relationship] started, but three weeks after 9/11 the signs were there,' she says. 'So I'm going to assume it happened almost immediately.' Mary, who lives alone on the farm that she and her husband were decorating as their dream home, adds: 'In a sense I would say she "bought" him. And if I had $5million, I think I could do a little better than him.' The most bitter family disputes have involved the relatives of unmarried victims who had not prepared for their mortality as they were only in their prime. 'One of the problems we had was that only 20 per cent of the victims had wills,' says Feinberg. Lisa Goldberg's partner, Martin McWilliams, would surely be appalled at the tangled legacy he left his tiny daughter, Sara, and the corrosive financial struggle which has faced her mother, a paramedic. The couple were not married, and McWilliams, a fireman, left no will. Having seen the devastation near her husband's fire station on TV and waited all day for news, Goldberg answered the door to three of his colleagues the evening of the attack. They told her that Martin had been crushed to death as he ran from the North Tower. 'I remember just dropping to my knees,' she says. 'It felt like someone had just cut me open and took my guts out.' Goldberg soon realised that her husband's family were not being supportive. 'I think I knew I was in trouble the first week,' she says. 'The whispers, the things that were said. I couldn't work it out then - but I knew something was coming. 'One of the fire fighters said: "Take pictures of everything he's got, all his clothes, everything in his house." I asked: "Why?" As things evolved, I began to realise - I wasn't getting any phone calls, I wasn't getting that type of respect as a spouse.' No automatic rights McWilliams's estate was entitled to $2 million, but as a domestic partner, Goldberg didn't have the automatic rights of the widows of other firemen. Her baby, Sara, would get everything as McWilliams's next of kin, but his family wanted to control the money. When Lisa applied for money on Sara's behalf from the Victim Compensation Fund, McWilliams's mother filed an objection. Hurtfully, she claimed that her son had not been in a relationship with Goldberg - despite the scores of carefree photographs of the couple together around the Goldberg home. The couple had been planning to move from a little apartment to a bigger house, and home videos show them playing with their baby. Bathing the child and cradling her in his strong arms, Martin glows with paternal pride and domestic bliss. Five years after 9/11, Goldberg is clearly a shadow of the woman beside him in those images, despite battling to provide a happy childhood for her daughter - now a bubbly, pretty little girl, who loves dancing. 'Sara is the best thing that came my way since he's not here,' she says. 'She's part of him, he didn't leave me here alone. She has pictures of her dad, and I tell her stories. Sometimes she asks me to tell a story about Daddy. His shirts that he used to wear, I have them hanging up. He is very much a part of this house.' Each month, Lisa must apply to court to access her daughter's funds for treats such as trips. She has to collect receipts to support her claims. Her legal battle continues, however, as she is trying to get a bill through Congress to access Martin's pension, like other widows. 'I've lost five years to this injustice,' says Lisa. 'It's not about the money. My existence with this man has been deleted. That's the hardest thing that I have to live with, besides him really being gone.' She adds: 'I know the last thing he did tell me, and that's what I hold onto the most. When he left that morning, he gave me a kiss and said: "I love you." Not everybody got that - so, that's what I hang onto.' The common strand to these women's stories is that money is not the most precious commodity. No one knows that more clearly than Eileen Cirri. She no longer speaks to her step-children, and her new-found wealth has brought no joy. A new sports car sits in her drive, attracting neighbourly resentment, but the gossips do not know that this is the car her husband dreamed of buying for their retirement, which she now uses mainly on her visits to tend his grave. 'Five years on, people's perceptions have changed,' she explains. 'You are in a fishbowl, with jealousy and vengeance coming at you. I was very surprised recently when pulling out of my driveway, my neighbours said something cruel, like: "There she goes again."' Eileen has come to terms with her husband's death and the destruction of her family, and generally ignores the catty comments she attracts. Yet there is one thing for which she would exchange all the money in the world. 'That morning, it was early and I was still lying in bed so I just said: "See you later,"' she remembers. 'If I could only have five minutes to say a proper goodbye.' |